Built Form as a Community Value: An Ethics of Architecture

Jaime Blosser, AIA

Global consumerism is slowly disintegrating our notions of place. On one hand, we have freeways and strip malls, big box franchises and tract homes. On the other hand, we have a demand for design and beauty that has made its way into all areas of our consumer culture but that is equally global: the iPod, the new Beetle, made-to-order mod pre-fab homes, computer wallpaper, IKEA, and Internet boutique stores are all products of this demand. A strip mall in one place could be anyplace. Purchasing objects from around the world via the Internet instead of buying them locally amounts to the same thing. Marketing images and aesthetics dislodge place and art. Jean Baudrillard speaks to this:

"...Disneyland as hyper-real world masks the fact that all America is hyper-real, all America is Disneyland. And the same for art. We have no more to do with art...as an exceptional form. Now the banal reality has become aestheticized, all reality is trans-aestheticized, and that is the very problem. Art was a form, and then it became....a value, an aesthetic value, and so we come from art to aesthetics--it's something very, very different."

The Hyper-Real in America

It is difficult to attach any cultural meaning to a place when there is no there there. This sense of dislocation feeds an underlying anxiety in contemporary American culture, a symptom of which emerges as a quasi-hysterical search for truth, resulting in many brands of fundamentalism. We are driven to search for meaning in the midst of the hyper-real. Architecture, whether through a global avant-garde or a quaint Disneyfication, often responds with more art as packaged aesthetic.

In 2000, I had come to face this squarely. The firm I worked for at that time, while giving me excellent training and opportunities, had found itself in a high-end resort niche. I was designing for two multinational corporations that planned to turn historic properties into high-end resorts. Having moved to Zuni, N.Mex., after graduate school, I had made my way to Santa Fe and had quickly grown to appreciate New Mexico's cultural and environmental uniqueness--its hidden mountain villages, old mission churches, and the smell of roasting green chile in the fall. I mourned the impact of global consumerism on this environment, yet as an architect I was responsible for building some of it.

Looking for alternatives, I discovered the Enterprise Foundation Frederick P. Rose Architectural Fellowship. I met Tomasita Duran of the Ohkay Owingeh Housing Authority at San Juan Pueblo. With a waiting list of 80 families, Tomasita was searching for ways to build new housing. We established an immediate rapport and managed to quickly put together a winning application.

An Alternative to the Hyper-Real

In August 2000, I began work at San Juan Pueblo, now called Ohkay Owingeh, which means "Home of the Strong People" in their native Tewa. The tribe had recently taken control of the housing authority and Tomasita, a tribal member, believed that her primary role was to make her community a better place for her sons. Her next priority was to build new housing appropriate for tribal members. We began work on what would eventually be called Tsigo bugeh Village, a low-income housing tax credit project.

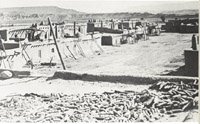

Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), c. 1920

Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), c. 1920We began talking about ways to approach new affordable housing. We hired Van Amburgh + Parés Architects and together walked the historic pueblo, which is laid out around plazas where tribal members still participate in ceremonial dances on ritual feast days. Antonio Parés had brought his compass and noted that the main plaza was situated exactly east-west, meaning it would line up with the path of the sun on the spring and fall equinoxes. This discovery immediately became the cornerstone for our new development-to learn from the ancient settlement patterns of the Ohkay Owingeh.

We also decided to ask tribal members directly what they wanted in a home. Residents had often complained to Tomasita that the typical HUD home was not suitable to the tribal way of life. We held design meetings with tribal members, bringing in pueblo storytellers, elders, and tribal leaders to talk about growing up in the old pueblo. We also asked the people attending the meetings about their values: family, social, and spiritual. We asked what materials were important to them and how their homes could support their lifestyles. At first, it was difficult to get any opinions out of people; no one had ever asked them these questions before.

Historic Design with a Modern Flair

We ultimately built 40 townhomes and a community center, which were completed in fall 2003. The homes were attached, two-story structures that surrounded two plazas, one of which was oriented to the equinox. The typology and proportions of the buildings were based on the historic pueblo, yet the design is clearly contemporary. While traditional settlement patterns clearly informed the site planning, we wanted a sense of tribal ownership to be apparent at every scale.

During the community design meetings, we discovered that on the traditional feast days the women typically worked in cramped kitchens preparing food for hundreds of people, which was then served throughout the day in cramped dining and living rooms. We designed open floor plans to accommodate more flexibility on these busy days. Antonio also designed various types of sunshades throughout the development and oriented the buildings for passive solar heating. The Rose Fellows helped to build two hornos, or outdoor bread ovens, under the guidance of a traditional artisan. We gave the elementary schoolchildren ceramic tiles and glaze and hung a fired tile at each entry door.

Tsigo bugeh Village, Equinox Plaza

Tsigo bugeh Village, Equinox PlazaThe main historic plaza's alignment to the equinox is based on Tewa cosmology. The Ohkay Owingeh believe that their pueblo is at the center of the world. The sun at noon of the equinox is situated at the middle of time--the exact middle of the day and the exact middle of its seasonal path through the sky. The middle of time occurring at the middle of the world is a potent combination. Tribal stories describe the sun as impregnating a maiden during the equinox. The agricultural cycle attests to this potency in the the spring planting and fall harvesting of nature's fruits at the time of equinox. The ritual calendar of the Ohkay Owingeh celebrates the equinoxes as well as the solstices. The tradition of preparing and serving food on feast days--to family, friends, and strangers--reflects a profound gratitude for the generosity of the natural world.

Spirituality, Design, and Culture

As humans, our reality is not wholly in the material world. We are creatures who exist on an intellectual and spiritual level, which gives us the ability to express our reality into philosophies, stories, and works of art. The objects we make are not and never have been purely functional. Yet contemporary architects rarely have a language with which to ask our clients about this other reality.

Tsigo bugeh Village was successful because we opened a discussion of underlying cultural values and were able to manifest some of them in architecture. Communities, through dialogue, can find ways to reinstate local ideas of place. As architects, we are trained to look for meaning in the built manifestations of human culture. Antonio and I immediately sensed the importance of the historic pueblo's alignment to the equinox, without even knowing very much about Tewa cosmology. I now see that because of my training as an architect, I can act as an effective participant in placemaking that reflects a community's values.

“You must first position the arms and legs and, by the position of the heart, the middle place will become known.” --Zuni saying

In school I was taught that taking a stand, or having a "parti," was an essential act of design. Good design protects the most basic elements of our existence--our ability as humans to define our place, to stake out who we are and what our reality is. Architecture has an ethical responsibilty to take a stand for place, local culture, and beauty. In this way, we can quietly define the middle place as what is real amongst so much of the hype(-rreal) surrounding us.

(Article may be found at www.aia.org)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home